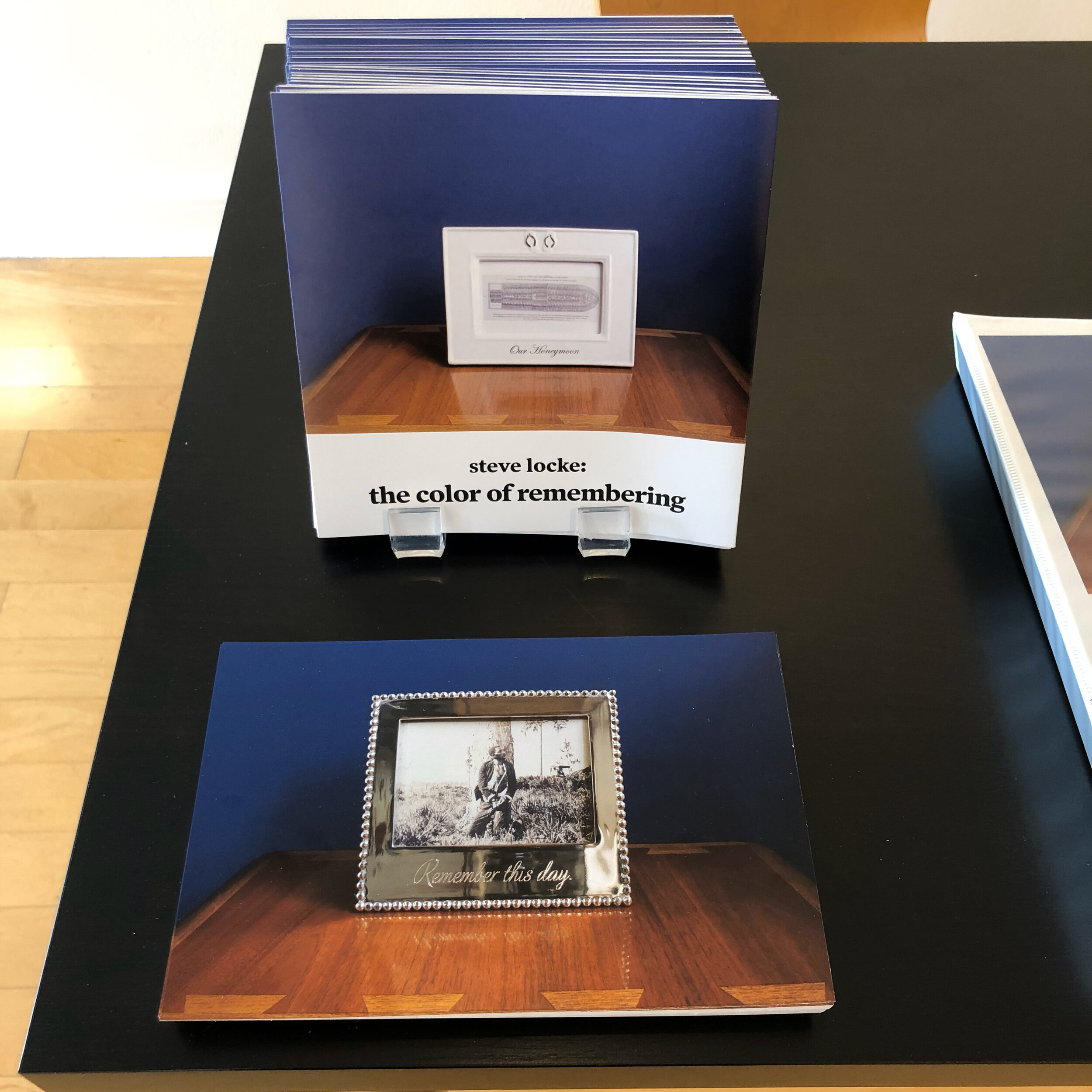

Purposeful Remembering

Steve Locke powerfully deconstructs the forgetting and remembering of the American past in the exhibition the color of remembering. He demands that we resist the willful amnesia around inconvenient evidence that all too many times shapes the study of American history as we connect the past to the present.

Silver, bright, and commonplace, the picture frames in Locke’s series Family Pictures would be invisible in a living room on a mantelpiece or an end table full of posed photos of family and friends. However, the images immediately force the viewer out of this safe space. The first image in a cheery frame speaking of cruises and a well-earned honeymoon is an eighteenth century engraving of a slave ship, The Brookes. This jarring composition of the happy commonplace and the murderous environment of the middle passage immediately evokes that for many the coming to America was not about freedom, but of bondage and violence. It is a story of those just beyond the frame as well: the captain and crew of the slave ship, the agents and auctioneers who made the sales, and the bankers who financed the voyage. In addition, White abolitionists researched and circulated the image of a slave ship in their crusade to end the slave trade.

Many of the remaining images are of lynching during the Jim Crow era. Ida B. Wells wrote in 1894 in her anti-lynching book A Red Record that “Lynch Law has become so common in the United States that the finding of a dead body of a Negro, suspended between heaven and earth to the limb of a tree, is of so slight importance that neither the civil authorities nor press agencies consider the matter worth investigating.” Wells argued that if White Americans could just see, just understand the violence, the majority would demand its cessation. Instead, many Southern journalists attempted to discredit her ideas and lynching continued.

Black bodies are not the only ones in Family Pictures. Surrounding the dead bodies, crowds of White Americans proudly posed, men, women, and even children, for a picture afterwards. These photos were keepsakes, and seem to ask, as carved in one of the modern frames, “who wouldn’t want to be us?” For them, these were acts to commemorate, not to hide in shame.

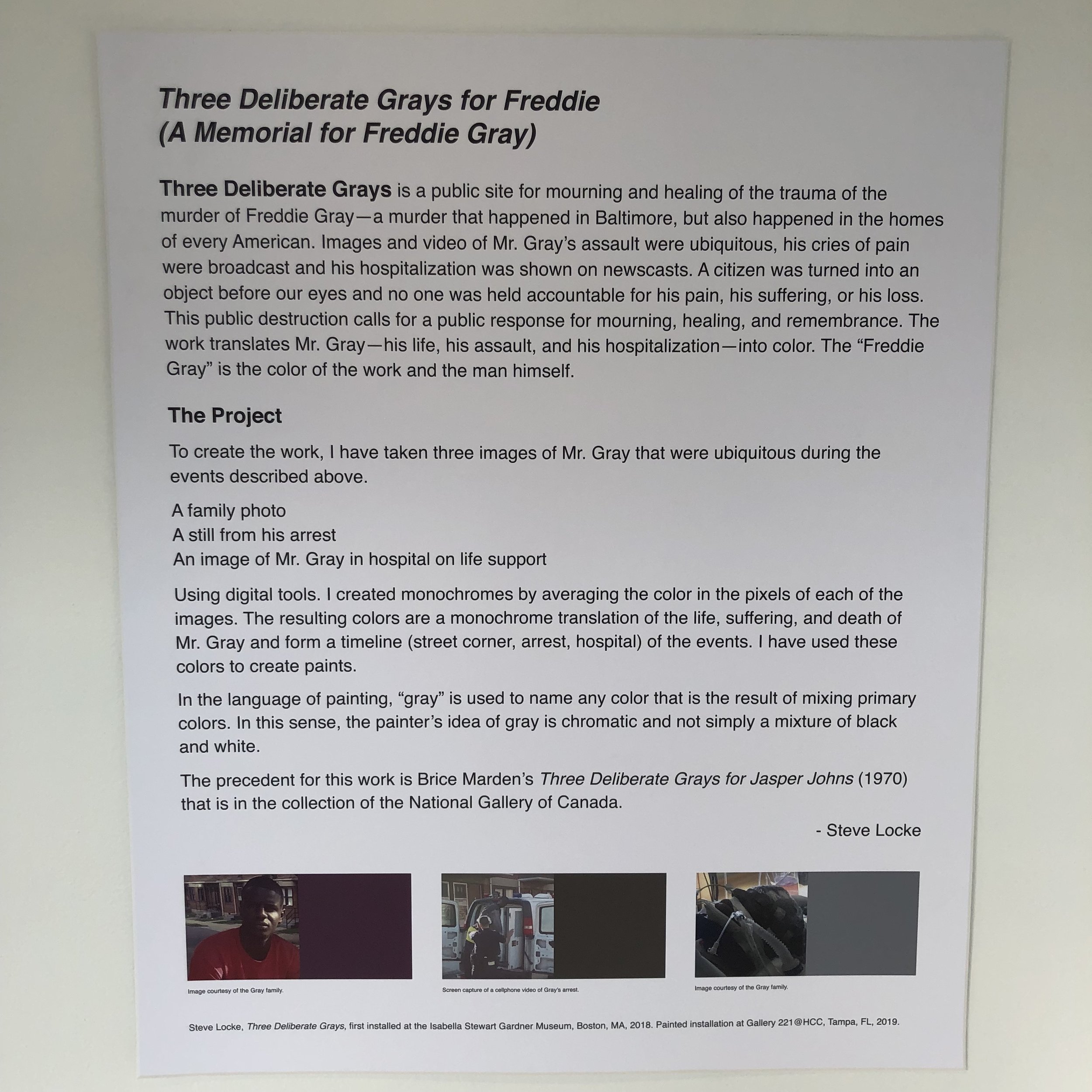

Consider, as you view the images, the middle-class American life of vacations, pictures on the wall, and honeymoons that the frames evoke. How do we choose what to commemorate or crop out of our pictures? What would Ida B. Wells say about the death of Freddie Gray, memorialized in Three Deliberate Grays for Freddie (A Memorial for Freddie Gray)? Locke’s work draws a powerful line from the American past to today, and makes us remember and face that this is all of our shared history, and its legacy is our shared present.

- John Ball, Professor for the Associate in Arts Program, HCC Dale Mabry Campus